When creating a new project using the rails new command, Rails automatically sets up three environments:

- development: Local development environment

- test: For running tests

- production: Production environment serving customers

In the earliest stages of a project, during the idea validation phase, engineers typically follow a straightforward workflow: write code, run tests, and deploy directly to production.

Business Phase One: Limited Customer Base Link to heading

As the product evolves and gains initial customers, maintaining code quality becomes crucial. This is when teams typically add a pre-release environment, commonly named “staging,” and implement a more rigorous workflow:

- Engineers develop new features locally (development environment)

- Run tests in CI (or locally) (test environment)

- Merge code to staging branch and deploy to staging environment for QA testing

- If no bugs are found, deploy to production for customer use

environments

├── development.rb

├── staging.rb

├── production.rb

└── test.rb

Business Phase Two: Growing Customer Base & Multiple Teams Link to heading

As the product gains market traction and the customer base grows, engineering teams expand from a few members to dozens or hundreds. With many people sharing a single staging environment, code conflicts become common when merging to the staging branch.

When conflicts occur, patient developers might contact the original author to resolve them. However, in global teams, time zone differences can make this process take a full day. This often leads to impatience, with developers resetting the staging branch, causing confusion and disappearing features.

To reduce code conflicts and communication overhead, many companies create dedicated deployment environments for each team. This isolation ensures that issues in one team’s environment don’t affect the entire company’s development progress.

| Instance | Git Branch | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| production | release/xxx | Production environment for customers |

| demo | demo | Sales demonstrations |

| staging | main / next release branch | Pre-release regression testing |

| staging-1 | staging-1-branch | “Panda” team environment |

| staging-2 | staging-2-branch | “Suicide Squad” team environment |

| staging-3 | staging-3-branch | “Galaxy Fleet” team environment |

| staging-4 | staging-4-branch | “Deep Sea Siren” team environment |

| staging-… | staging-6-branch | Additional team environments |

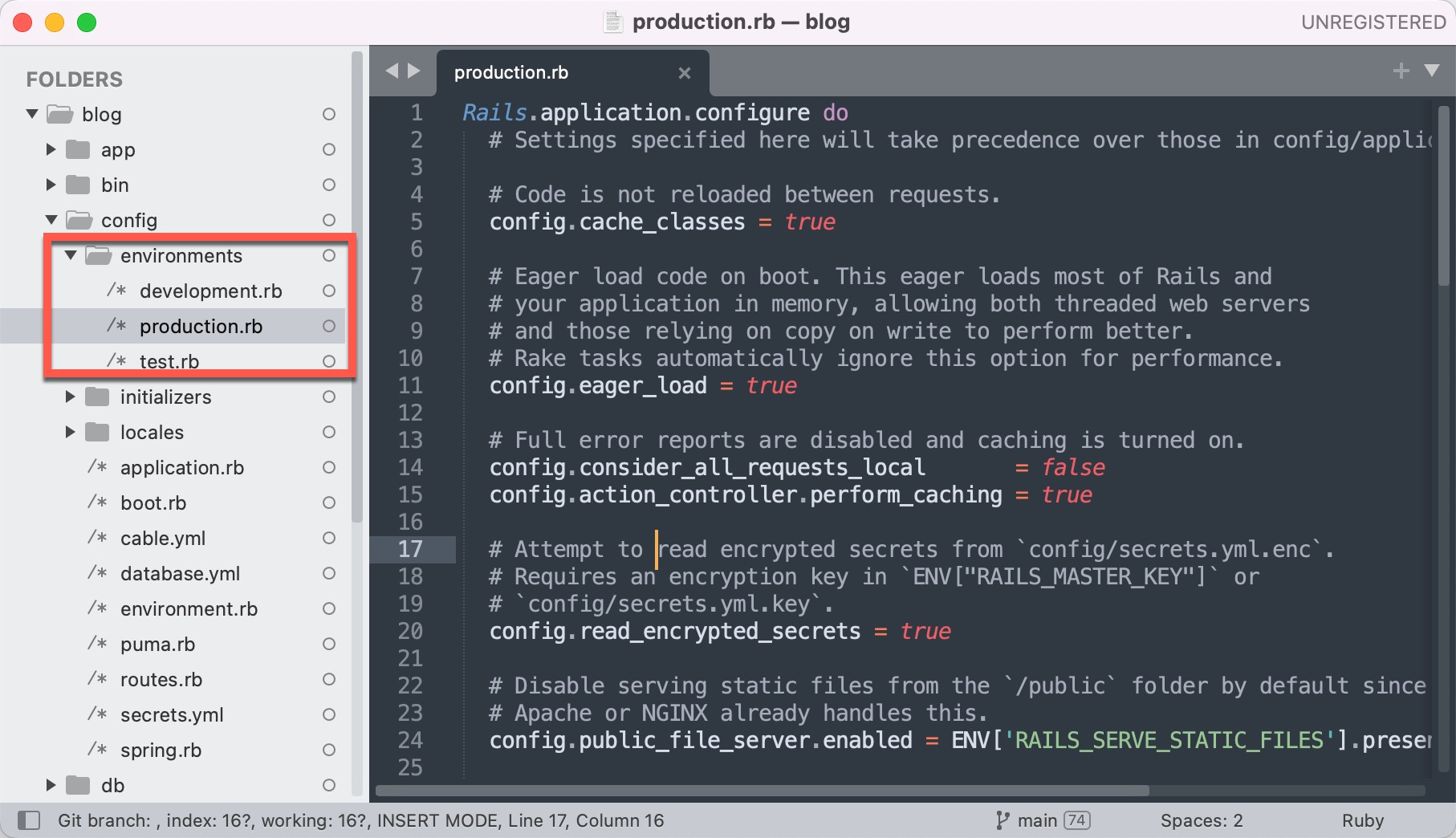

As the engineering team grows, so does the need for Rails deployment environments. To create six deployment environments (staging, staging-1 through staging-4, demo), we need to create six configuration files in Rails’ config/environments directory, following Rails’ recommended configuration style.

> tree environments

environments

├── demo.rb

├── development.rb

├── test.rb

├── production.rb

├── staging.rb

├── staging-1.rb

├── staging-2.rb

├── staging-3.rb

├── staging-4.rb

...

However, this is just the beginning. We also need to add database configurations for these six new deployment environments in config/database.yml:

default: &default

adapter: postgresql

database: <%= ENV['DATABASE_NAME'] %>

username: <%= ENV.fetch("DATABASE_USER", 'postgres') %>

password: <%= ENV['DATABASE_PASSWORD'] %>

port: 5432

production:

<<: *default

demo:

<<: *default

staging-1:

<<: *default

staging-2:

<<: *default

staging-3:

<<: *default

Additionally, if engineers have defined configurations in constants, we need to search globally for Rails.env to ensure all new deployment environments have matching assignments. This is particularly important for variables defined in obscure places, as missing configurations can cause deployment failures.

For example, Redis addresses might be defined in constants:

# config/initializers/sidekiq.rb

case Rails.env

when :demo

REDIS_HOST = 'redis-demo.3922002.redis.aws.com:6379'

when :staging-1

REDIS_HOST = 'redis-s1.3922002.redis.aws.com:6379'

when :staging-2

REDIS_HOST = 'redis-s2.3922002.redis.aws.com:6379'

...

Defining configurations in constants is error-prone. Most engineers extract environment-specific configurations into separate files using libraries like “rubyconfig/config”1. If the team uses such libraries, we need to add configuration files for new deployment environments:

config/settings/demo.yml

config/settings/production.yml

config/settings/staging.yml

config/settings/staging-1.yml

config/settings/staging-2.yml

config/settings/staging-3.yml

config/settings/staging-4.yml

...

This approach has several drawbacks:

-

Even with comprehensive internal documentation, the process is labor-intensive and costly.

-

Creating new deployment environments requires modifying constants in existing code, which is risky and can lead to bugs.

-

Poor security: configurations containing client secrets, tokens, and private keys could be exposed if the code is leaked. Docker images created with this approach contain mixed configuration information, creating security risks.

Despite these limitations, this native Rails solution can work for a while.

Business Phase Three: Multi-tenant Solutions, Private Deployments, and Large Development Teams Link to heading

In early project stages, there’s typically only one production deployment environment:

- For consumer-facing products (To C), one production deployment serves all customers.

- For enterprise SaaS products, early designs use multi-tenant architecture, with one production deployment serving all enterprises.

This leads many developers to assume “there is only one production deployment environment.” However, this assumption breaks down as the business grows.

National Security Requirements: Some countries require citizen data to be stored in domestic data centers. Apple iCloud maintains data centers in both the US and Guizhou, China, running the same code in production mode in both locations. TikTok deploys on Oracle Cloud in the US and in their own data centers in China, both in production mode.

Enterprise Security Requirements: Large customers often demand private deployments (self-hosted). Alibaba Cloud sells the same code to government agencies, China Telecom, and public security systems, deploying in their respective data centers.

Open Source Project Deployments: GitLab, an open-source code management platform, serves small to medium customers through gitlab.com accounts, while larger customers with their own infrastructure deploy GitLab in their private networks with restricted IP access.

A real-world SaaS deployment scenario might look like this:

| Running Instance | Git Branch | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| production | release/100* | Multi-tenant SaaS on public cloud |

| production-gov | release/101 | Government client, private deployment |

| production-cnpc | release/99 | CNPC client, private deployment |

| production-china-police | release/100 | Chinese police, private deployment |

| production-us-police | release/100 | US police, AWS deployment |

| production-huawei | release/100 | Huawei client, private network |

| demo | demo | Sales demonstrations |

| staging | main / next release branch | Pre-release regression testing |

| staging-1 | staging-1 branch | “Panda” team development |

| staging-2 | staging-2 branch | “Suicide Squad” team development |

| staging-3 | staging-3 branch | “Galaxy Fleet” team development |

| staging-4 | staging-4 branch | “Deep Sea Siren” team development |

| staging-… | staging-… branch | Additional team development |

Note: Release branches: In Trunk-based development2, QA (or CI) periodically creates deployment branches from the latest main branch, runs tests, and if no bugs are found, the branch can be deployed to production.

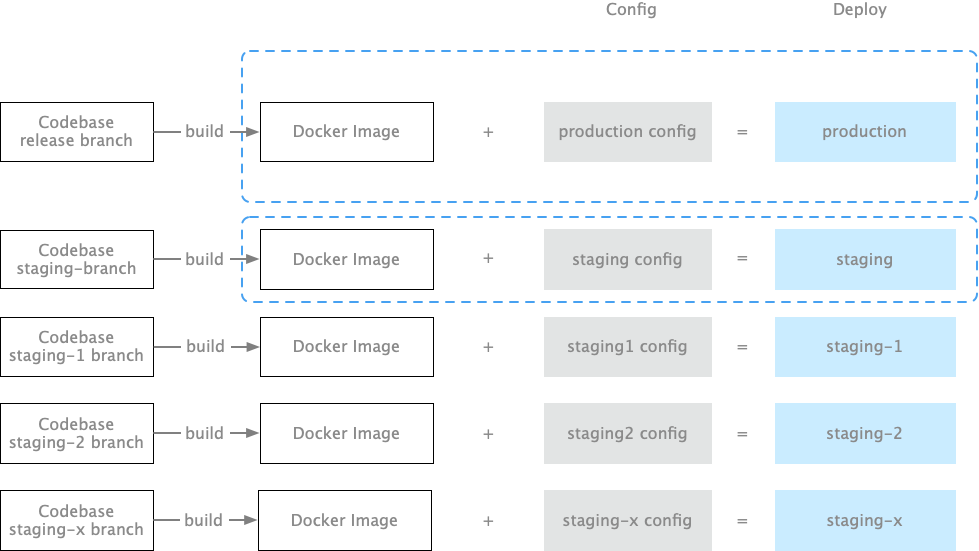

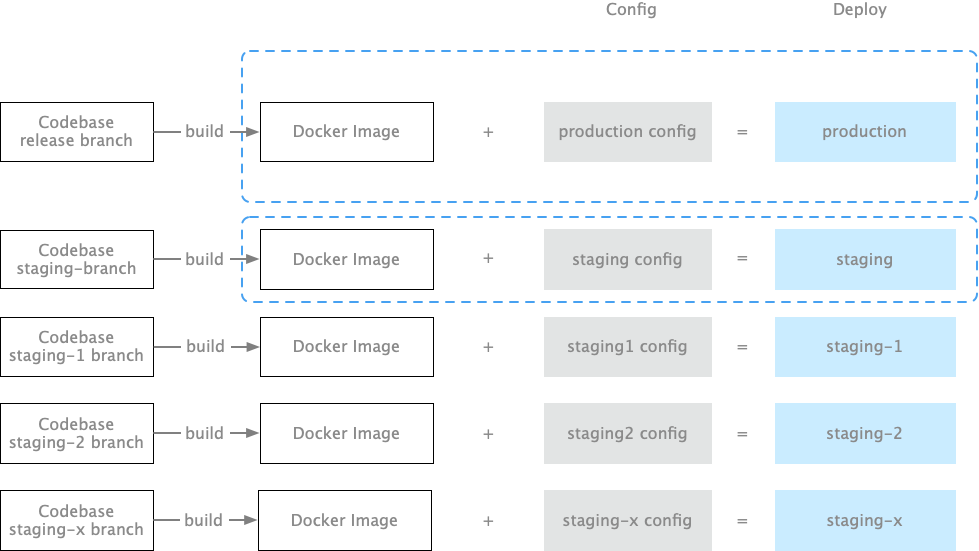

With multiple production environments, should we mix all client configurations into the code? Obviously not! Clients wouldn’t allow it! Therefore, the industry consensus is that code should be stateless, with configuration information stored separately, allowing new deployment environments to be created without changing a single line of code.

Concept: Deployment Link to heading

When there’s only one production environment, we can use the term “production environment” to refer to it. However, when GitLab is run by thousands of enterprises with countless production instances, the term “production environment” becomes meaningless in communication3.

For more precise expression, in the latter part of this article, we’ll use the concept of deployment to refer to an instance of code running in a data center.

Meanwhile, the files in Rails’ config/environments directory (production.rb, staging.rb, development.rb, test.rb) we’ll call code running modes.

For example, when GitLab is deployed to Huawei’s private network, we say “GitLab has created a deployment in Huawei’s private network, running in production mode.”

The 12-Factor Application Link to heading

Heroku’s article “The 12-Factor Application4” outlines 12 principles for designing SaaS applications, which remain the gold standard to this day.

Principle 1: One Codebase, Multiple Deployments Link to heading

Each application’s codebase can have multiple deployments. Each deployment represents a running instance of the application, typically including one production environment and one or more pre-release environments.

Principle 2: Explicitly Declare Dependencies Link to heading

The same code should have consistent dependencies and behavior across different machines:

- JavaScript uses npm or yarn to manage library dependencies

- Ruby uses Bundler to manage library version dependencies

- Docker packages both code library dependencies and operating system dependencies, ensuring code runs consistently across different environments

Principle 3: Store Configuration in the Environment5 Link to heading

The 12-Factor App recommends storing application configuration in environment variables. Environment variables can be easily modified between deployments without changing any code.

Docker

Docker allows you to store configuration in environment variables, creating different instances (containers):

docker run --name postgresql \

-e POSTGRES_USER=myusername \

-e POSTGRES_PASSWORD=mypassword \

-p 5432:5432 -v /data:/var/lib/postgresql/data \

-d postgres

Helm

Helm6, a Kubernetes application package management tool, follows the first three principles of 12-Factor. It has three core concepts: chart, config, and release.

- chart is a template, stateless

- config is configuration information

- release = chart + config. When combining template and configuration, a deployment instance is created

Almost all excellent open-source software follows 12-Factor principles. Beyond architectural excellence, I suspect the authors knew from day one that their software would be used by thousands of companies, requiring separation of code and configuration.

While our code won’t be deployed to thousands of companies, adopting 12-Factor principles helps us quickly create and maintain dozens of deployments. DevOps becomes more efficient, business developers can focus on development, and sales can confidently demonstrate features, all without interference.

Implementing 12-Factor Principles Link to heading

Step 1: Make code stateless, with all configuration information coming from environment variables.

For example, database configuration should come from environment variables:

# config/database.yml

# ...

production:

<<: *default

database: <%= ENV['DATABASE_NAME' %>

host: <%= ENV['DATABASE_HOST'] %>

password: <%= ENV['DATABASE_PASSWORD'] %>

...

Sidekiq configuration also comes from environment variables:

# config/initializers/sidekiq.rb

Sidekiq.configure_server do |config|

config.redis = {

host: ENV['REDIS_HOST'],

port: 6379

}

end

# ...

Any logic related to deployment should get its configuration from environment variables:

class OauthController < ApiController

def redirect

redirect_to(ENV['GOOGLE_OAUTH_URL'])

end

end

Step 2: Prepare configuration files.

Create configuration files for staging-1, staging-2, staging-3, staging-4, demo, production, production-gov, production-china-police, production-us-police, etc.

If using AWS, store deployment configurations in AWS Systems Manager Parameter Store and sensitive information in AWS Secret Manager:

# Create staging-1 configuration

aws ssm put-parameter \

--name "staging-1-configuration" \

--value "parameter-value" \

--type String \

--tags "DB_HOST=xxx,DB_USER=xxx,DB_PASSWORD=xxx,REDIS_HOST=xxx,GOOGLE_OAUTH_URL=xxxx"

If using Kubernetes, store deployment configurations in ConfigMap and sensitive information in Secret:

# Create staging-1 ConfigMap

kubectl create configmap staging1-config-map \

--from-literral="DB_HOST=xxx" \

--from-literral="DB_USER=postgres" \

--from-literral="DB_PASSWORD=xxx"

# Create staging-1 Secret

kubectl create secret generic staging1-secrets \

--from-literral="GOOGLE_CLIENT_ID=xxxx" \

--from-literral="GOOGLE_CLIENT_SECRET=xxxx"

Step 3: Run all deployment instances in production mode.

Almost every engineer has encountered similar problems:

Why does code run on a colleague’s machine but not on mine? Why does code run locally but not in staging? Why does code work in staging but cause problems in production?

Many issues stem from differences between local, testing, and production environments. For example, local development might use MacBook while production servers run Ubuntu; local development might use SQLite while production uses PostgreSQL; local development might use memory for caching while production uses Memcached. The 12-Factor App calls these differences “Dev/prod parity”7.

To eliminate differences between deployments, run all instances (production, production-huawei, demo, staging-1, staging-2, staging-3, etc.) in production mode:

RAILS_ENV=production rails s

Step 4: Combine code and configuration to create deployments.

If using Capistrano for deployment:

Code + Configuration = Deployment

If using Docker:

Docker Image + Configuration = Deployment

If using Kubernetes, injecting different configurations into Pods creates different deployments:

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

labels:

name: webapp

name: webapp

namespace: default

spec:

containers:

- name: web-app

image: web-app:staging-1

envFrom:

- configMapRef: 👈 Look here

name: staging-1-config-map

- secretRef: 👈 Look here

name: staging-1-secrets

Advantages Link to heading

-

Stateless code can be reused. Creating new deployments only requires new configuration files, saving time and effort.

-

Code and Docker images don’t contain sensitive information. Code leaks don’t increase security risks.

-

Facilitates private deployments.

-

Different deployment configurations can have different access permissions, e.g., restricting access to production deployment configuration to specific teams.

-

All deployments run in production mode, eliminating differences between deployments. (Teams can decide based on their specific needs. Some prefer running staging deployments in staging mode.)

Disadvantages Link to heading

Monitoring tools like NewRelic, Datadog, and Sentry typically attach environment information to monitoring data for filtering. In the second approach, all deployments run in production mode, causing all monitoring data to be mixed under “production.” During incidents, engineers can’t identify which deployment has problems.

Solving Monitoring Tool Issues

Datadog, New Relic, and Sentry provide interfaces for customizing deployment names. For example, Datadog’s syntax is:

Datadog.configure do |c|

# ...

c.env = "your-preferred-deployment-name"

end

Therefore, we can introduce a new variable “DEPLOY_ID” in different deployment configurations (staging-1, staging-2, staging-x, production-x) to declare deployment names and pass them to monitoring tools.

Passing DEPLOY_ID to Datadog8

Datadog.configure do |c|

c.env = ENV['DEPLOY_ID'] # prod / staging-1 / demo / prod-huawei

# ...

end

Passing DEPLOY_ID to Sentry9

Sentry.init do |config|

#...

config.environment = ENV['DEPLOY_ID'] # prod / staging-1 / demo / prod-huawei

end

Passing DEPLOY_ID to New Relic10

# config/initializers/newrelic.rb

NEW_RELIC_ENV=ENV['DEPLOY_ID']

NEW_RELIC_LICENSE_KEY=ENV['NEW_RELIC_LICENSE_KEY']

...

This ensures proper display in monitoring tools.

Acknowledgments Link to heading

The solutions in this article come from the practical experience of Workstream colleagues and former SAP colleagues. I’ve merely organized and documented them.

Special thanks to Louise Xu, Felix Chen, Vincent Huang, Teddy Wang, and Kang Zhang for their review and feedback.

References Link to heading

-

Ruby Gem: rubyconfig ↩︎

-

GitLab had to invent new concepts to distinguish between deployment names and running modes. This was the original design proposal. ↩︎